Preservation Idaho Intern Savannah Willits recently explored the controversy surrounding Boise’s failed downtown mall, and it’s role in the larger story of Boise’s urban renewal and identity. The following is the second of a two-part series of blogs resulting from Savannah’s research. Read the first part, The Impact of Buildings Unseen.

Historical Counterfactual

Since the age of urban renewal, mixed-use development principles have guided the urban planning decisions in Downtown Boise. However, the unseen building’s presence—the regional shopping mall never built—lingers over the city.

The absent downtown mall has resulted in a downtown that is not now dependent on a dying retail model nor in desperate need of major revitalization. From the rise of abandoned mall photography to the dramatic decline of major retailers, the mall’s unfilled promise of prosperity has been well documented. For example, JCPenney, Macy’s, Forever 21, and Victoria’s Secret, all anchor stores at Boise’s Towne Square Mall, have filed for or are on the brink of bankruptcy.

Similarly, Boise Dev and the New York Times has reported that Green Street Advisors, a firm that rates malls in the United States, forecasted that “half of all department stores” would close in the next five years, even before the COVID-19 pandemic hit. This pandemic has only exacerbated the already weakened economic livelihood and exploited the archaic reach of major brick-and-mortar retailers due to the rise of the online retailers.

In an alternative timeline in which the downtown mall is built, Boise’s retail situation would have most likely resembled Salt Lake’s City Creek or Spokane’s River Park Square. Both regional shopping centers have required redevelopment efforts in the form of economic revitalization funding and amenity additions and will continue to require rehabilitation to remain relevant.

Similarly, if the regional shopping mall had been built downtown, it would have experienced a higher density of retailer casualties. As of right now, only three retailers (Walla Walla Clothing Co, Loft, and Maven) have announced they will not reopen, while at least five mall stores, many of them anchor institutions, are desperately grappling with bankruptcy on top of an already dying mall model.

There are incredibly high odds that this “alternate universe Boise” would be facing immensely worse economic costs and a bleak future at this exact moment in time. Instead of celebrating a long list of national accolades, the center of downtown Boise would be in desperate need of radical revitalization. Therefore, the existing sustainability of Boise's mixed-use scene owes its dues, in a large degree, to the failed mall.

Overall, the major lingering impact of the absent mall was that it successfully persuaded the Boise community and leadership to bypass a failed method of redevelopment and instead pursue a mixed-use development approach. It was a blessing in disguise. Rather than being passive or apathetic observers of Boise’s evolving identity, community members such as those who participated in the Preservation Coalition, citizen advisory committees, and the planning entities actively took part in creating a Boise that values economic sustainability, historic preservation, and progressive urban planning practices. Boise’s mixed-use redevelopment plan, cemented during the urban renewal phase, successfully avoided the adverse outcomes of the regional shopping malls that haunt many of America’s metropolitan areas today.

(Click on the right side of the photos above to see more.)

Photos:

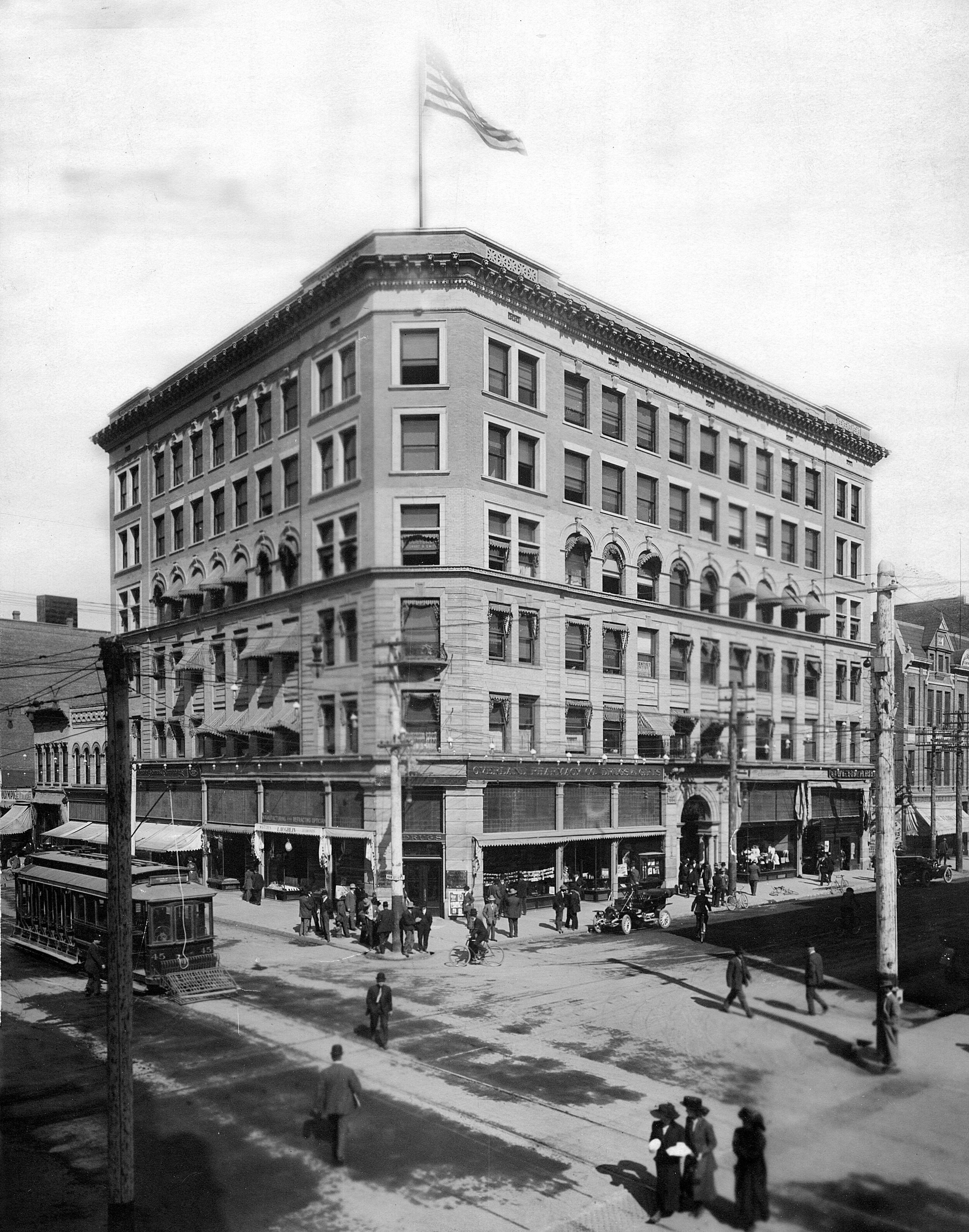

The cornices on the historic Eastman Building. 8. View of Main St. in the 70s.

The historic Eastman Building burning in 1987. 9-10. The historic Egyptian Theatre

The historic Sonna Building. 11. The historic Mode Building as seen today.

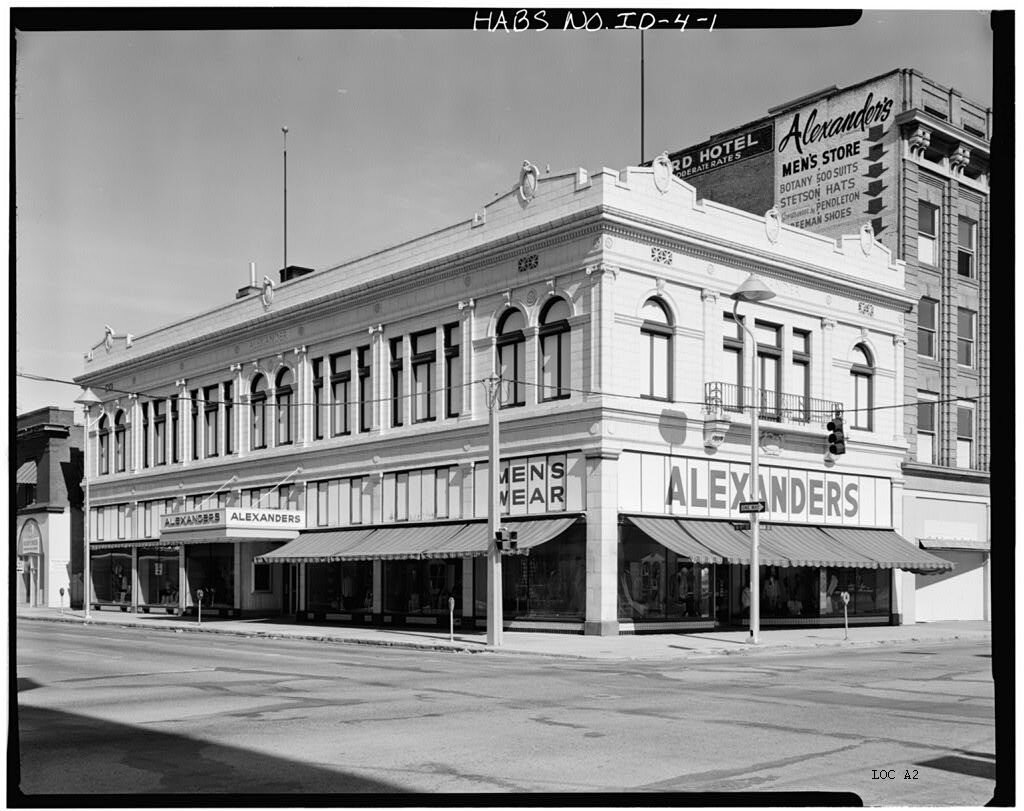

The historic Alexander’s Clothing Store. 12. The historic Hotel Boise (Hoff Building)

View of the Sonna Building and Alexander’s Clothing Store.

Conclusion

The impact of the historic buildings that were once jeopardized by the mall proposal have continued to be architectural anchors downtown. These buildings not only provide architectural flavor and diversity in style but also embody Boise’s historical duration. Had these buildings been demolished to create room for a mall architecturally, Boise would appear more adolescent in age and sophistication, compared to other peer northwest cities. Similarly, Boise’s layout and image would have been dominated by architecture of the 1970s and beyond, as well as barren surface parking lots in order to serve the large regional shopping mall. Incidentally, by remaining seen, these buildings provide depth and maturity as established urban anchors.

Moving forward, Boise’s ever-changing fears, desires, and values will continue to evolve and will likely become more divisive. As new buildings are envisioned, the skyline rises, and Boise grows in both age and size, conversations about embedding the community’s long-term values into present-day growth are vital. Such as in the case of the proposed downtown mall, these conversations and resulting outcomes will likely be the difference between a long-lasting mistake and future prosperity.

Overall, the legacy of the buildings seen and unseen has a tangible impact on the economic, social, and spatial outcomes. Therefore, it is critical to understand the balance between the reimagined visions and the dust of demolition. Equally important is to understand the community’s legacy of protection, conservation, adaptation, and rebuilding. Boise’s self-proclaimed mission of livability depends on this delicate balance, especially as our community grows.